Hillary and Clinton Scribe Lucas Hnath on Why He'll Leave the Room If the First Couple Comes to the Show

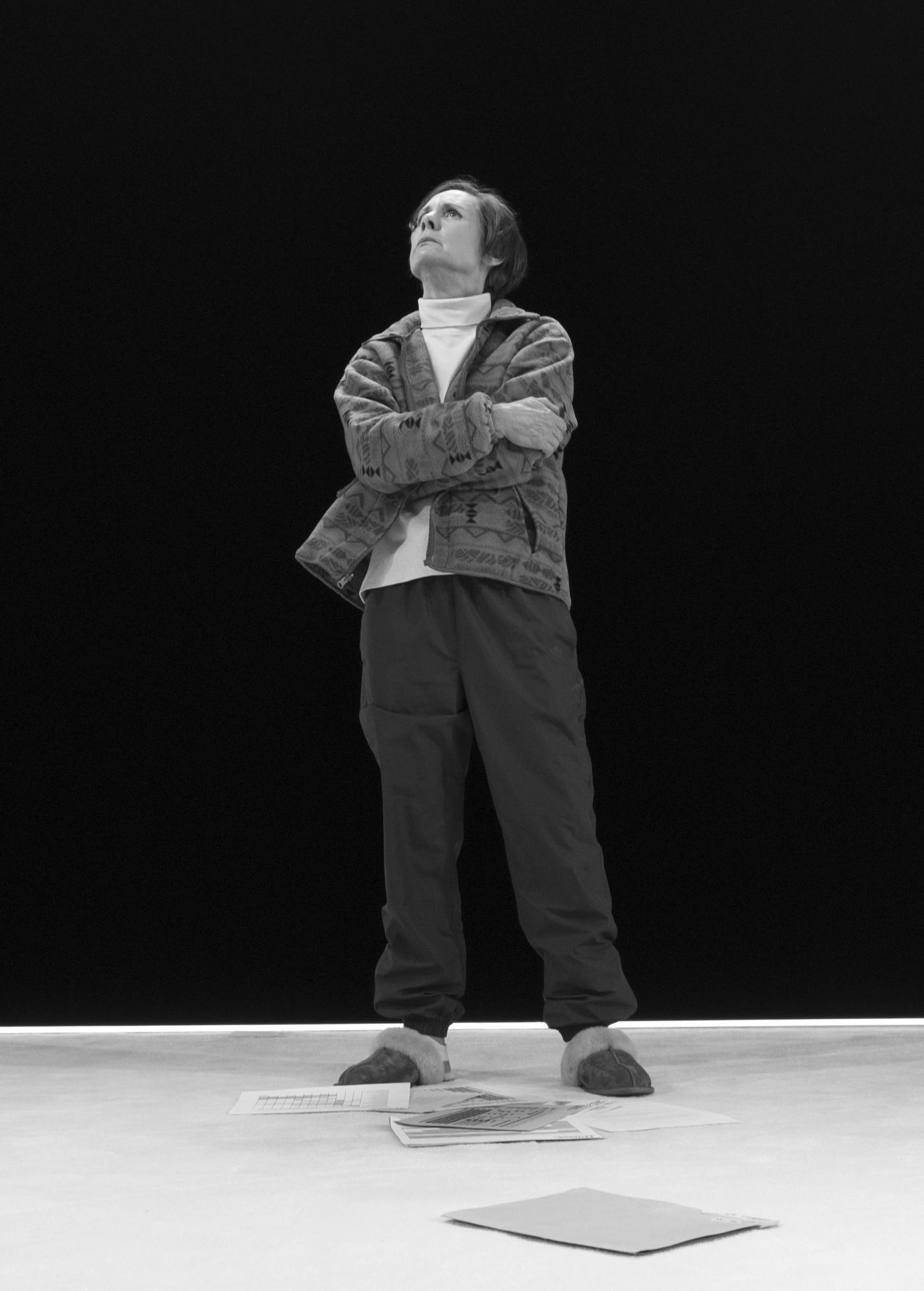

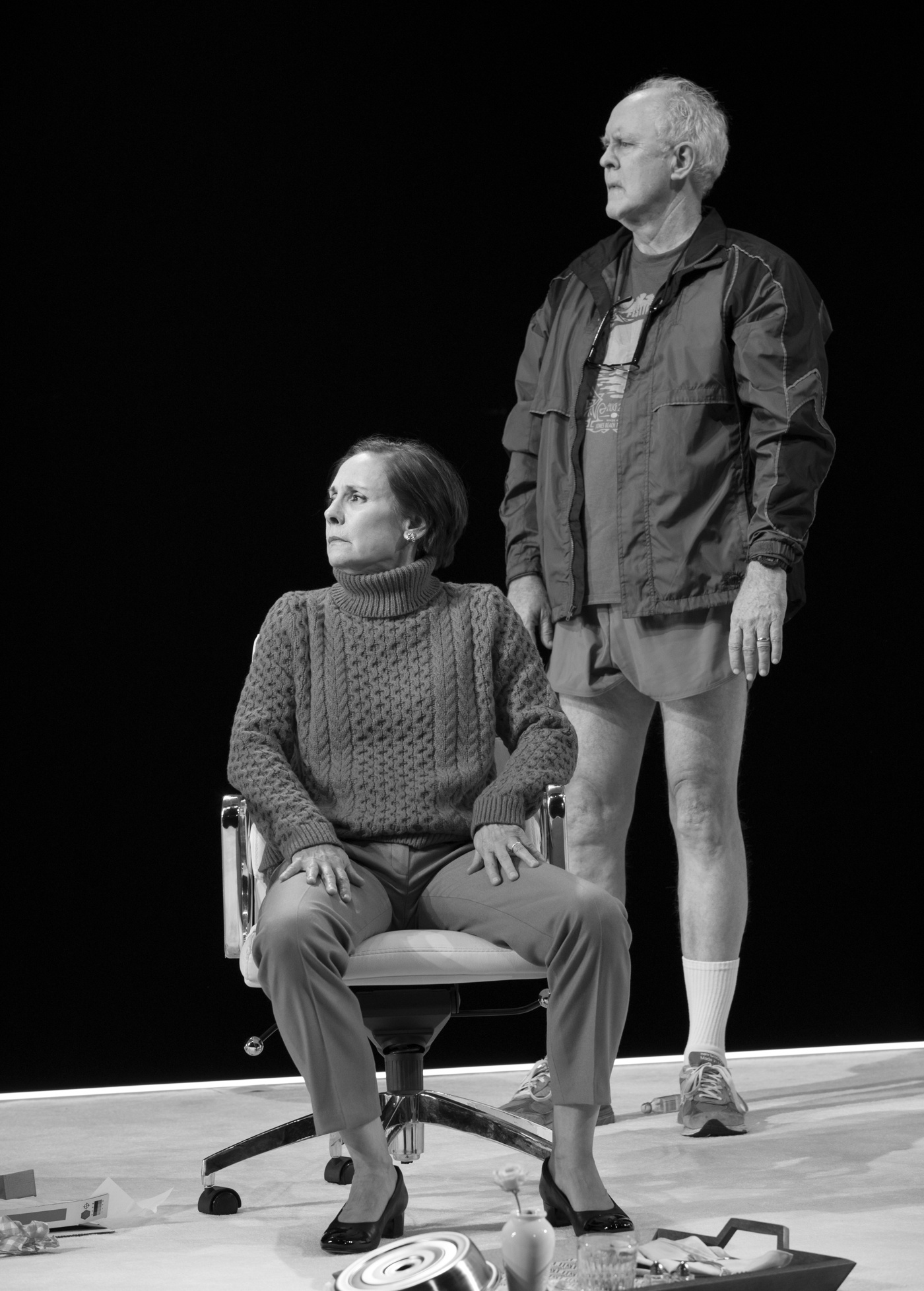

(Photos by Caitlin McNaney for Broadway.com)

Despite its title, Lucas Hnath’s Hillary and Clinton is not a bio-play. The piece, directed by Joe Mantello and starring Laurie Metcalf and John Lithgow, is a “mythic” version of the first couple in an alternate reality. Written in 2008 and reworked more recently, the play grapples with the politics of marriage and power and the pull of charisma. Hnath received a 2017 Tony Award nomination for Best Play for A Doll’s House, Part 2, which, this year, is the most produced play in America. His other plays include Red Speedo, The Christians, A Public Reading of an Unproduced Screenplay About the Death of Walt Disney, Isaac’s Eye and Death Tax. His drama The Thin Place will be seen off-Broadway next year, and his new work, Dana H. (which is a real-life story based on his mother), will premiere in Los Angeles this summer. Here, Hnath talks about the internal debate that sparked Hillary and Clinton, which opens at the Golden Theatre on April 18.

What inspired you to write Hillary and Clinton?

I think it was the Iowa caucuses I was watching on C-Span. I was watching these two people argue with each other about who to vote for. I don't even remember the specifics of what they were saying, but if I can piece it back together it was something along the lines of: Who seems like a nice person? Who seems authentic? Who seems like they're telling the truth? A lot of things that you don't really have evidence to verify any of it. It seemed that a lot of decisions were being made on somewhat specious grounds. It made me go back and think about when people are deciding who to vote for, how much is actually based on hard evidence versus an emotional response. That was the beginning of a train of thought that took me to this play.

What is at the root of the Clintons’ relationship that interests you?

Among other things, there's a debate happening that has something to do with thinking versus feeling. I think it was one of the earlier sections of the play where I wrote an argument between Bill and Hillary about how she should be running her campaign. Bill was making a case for an appeal to emotions, and Hillary was making a case for appealing to people's ability to think critically. I think in this marriage, there is also a fight between thinking versus feeling. That might be a root that resulted in the play because that's a fight I'm having in my own head all the time. I'm very suspicious of feelings; I don't trust them.

You wrote this play more than a decade ago. What made you want to come back to it?

I had written it in 2008. This was well before I was a playwright who—forget having representation—nobody read my plays back in 2008. [laughs] I was just writing plays and throwing them into a drawer and going on to the next one. By the time anybody would read them, this was a play that was quite old for me. I wasn't really showing it to people. The first production of the play happened in Chicago. [The play premiered at the Victory Gardens Theatre, directed by Chay Yew, in April 2016.] That was the original version. But, not this past December but the December before, [producer] Scott Rudin emailed me one morning and said, “Can you send me Hillary and Clinton?” I sent it to him, and he called me and said he wanted to option the play. I said, “Well, it's a play that I feel very far from right now. I don't write like that anymore.” The original conception of the play had a lot of, for lack of better term, whimsy and quirk to it. I told him all the things that I didn't particularly like about the play, and he said, “Well, you could change those things if you want!” I had no intention of working on Hillary. I was happy to just let that play, sit and never go any further.

What changed?

I just had this moment—I went for a run up and down the Hudson, and started to hear the play in my head. I went home, opened a new document, and I just started writing the play again from memory. I felt free in the course of writing it again to change anything I wanted. It was a really exhilarating rewriting process. It was like having a second chance with a play. I'm proud of the prior version of it, but I felt like there was more that it could have done. The arguments could have been tougher.

The political landscape has changed wildly since 2008, but you haven't changed the basic structure and timing of the play.

Right. When I was doing this big revision, I was acutely aware that my brain would want to wink at or reference 2016. Anytime I was really conscious that my head was doing that, I would strip out those impulses. I would not follow that path because I suspected—and I think it's been confirmed—the audience will be thinking about 2016 while they're watching it. That's unavoidable. They're doing a lot of the work for me. For me to reference it would actually take you out of the moment of the play, which is set in 2008. I think it does take on more significance when you're watching a play about Hillary dealing with the possibility of losing 2008, and know that there's not just one loss. All the decisions that get made in 2008 feel like they are part of what might have led this person to what happened in 2016, if that makes sense. There is a line and one of the scenes where Barack says something like, “The decisions we make in this room are very important.” That's as much of a wink as I make to 2016.

You've written about many familiar figures and real people in your work. What draws you to that?

It's fun—the game of knowing that people are coming in with preconceived notions. It also applies to something like [the 2015 play] The Christians, too, where I'm picking a subject that I know people are bringing baggage to. Not that everybody's notions are uniform; people have different ideas they bring into the theater. But, with certain subjects that are really charged, you can start to study and figure out, “OK, a lot of people think this, and a lot of people think that.” What can I add to the conversation that upends or flips it or implicates the audience in a train of thought that maybe if they thought it through a couple of steps further, they'd realize, “Oh, I don't know that I like that idea so much.” You know?

What are some of those ideas in Hillary and Clinton?

I strongly suspect that the audience is coming in enjoying the character of Bill. And there's a couple of moments where the play says, “OK, you think this character’s fun. Yeah, he's kind of a bad boy.” But what was the actual result of that? When all is said and done, what are people remembering when they think of Bill? What's the legacy of Bill? And it's satisfying to see the audience catch up to that. And there's a moment in the play where I just lay it out.

The question really lands?

Yeah, a lot of people, when they think of Bill, the first thing they think of is, you know...his non-presidential activities.

What a way to put that.

It's troubling. When we vote, we are very attracted to the extroverts. And Hillary is an introvert. At least my version of Hillary—and again, I won't claim to know the real humans and can't really speak fully to them—what she, as positioned in the play, represents is kind of boring, you know? It's not attention-grabbing in the ways that maybe Bill was. And we get caught up in the exciting candidate. Again, I'm nervous about that impulse. I want a boring leader. [laughs]

How would you feel if the Clintons showed up at your play?

I mean... [very long pause]

Would you stay in the house or would you have to leave?

Oh, I would have to leave! I don't really want to see their reaction to it. I think it would be a very weird thing for them to watch because, at the same time, it's not really a play about them. It's a play about this sort of mystic version of them. I would be very nervous.

Would it make you nervous because of the liberties you’ve taken or is it something else?

That's part of it. I'm having my cake and eating it too, because I am saying things about their legacies that are not necessarily complimentary. Then again, it already makes me very nervous to watch my own plays. I watch them to do work. I go in with things I want to work on, things I want to listen for and figure out. At the moment the show's frozen, and there's no more work to be done, I have nothing to do. I hate that feeling of watching a play and not having a job to do.

It must kill you to have them published.

Oh, yeah. It feels like a death. It feels like the plays are getting put in a grave.